FATUOUS FERMENTATION; CAUSES AND REMEDIES

Defective wines, rare as they are, can be educational. This bottle of Galernau, a Loire Valley Cabernet Franc, made a poor impression in a recent tasting. Not only did it have the prominent nose and flavor of Brettanomyces, a yeast that spoils wine flavor, but also a strong fizz in the entry and mid-palate, what we recognized as secondary fermentation, an undesired one. The occasion provoked some thought on the subject.

Fermentation, usually mediated by yeast, is the process by which sugars in grape juice are converted to acids, CO2 gas and yes, that all important alcohol. It is an essential step in the creation of all wine. This of course, is the primary fermentation.

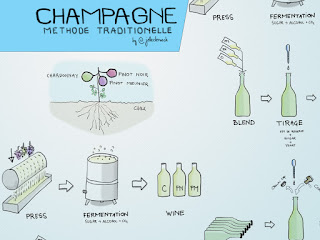

There are numerous types of secondary fermentation, two of which are common and well known, methode champenoise and malolactic fermentation.

In champagne making, still wine that has already been through primary fermentation and bottled, is supplemented by yeast, yeast nutrients and sugar. This provokes another fermentation, this time in the bottle. The end result is carbon dioxide gas which gives champagne its lovely bubbles.

Malolactic fermentation involves converting malic acid, a tart flavor naturally present in grape, to the softer tasting lactic acid. It can impart a buttery texture to the wine. Best known in the context of New World Chardonnay, malolactic fermentation occurs in the tank or barrel, and is provoked by the addition of specific bacteria that catalyze the process, Oenocuccus oeni being the most common. Some winemakers add the bacteria at the time of the primary fermentation along with the yeast, others do it afterwards. Regardless, malolactic is considered a form of secondary fermentation, a well accepted one.

On to unintentional secondary fermentation. This occurs if leftover yeast come alive and re-start sugar fermentation in the bottle, as in champagne. The gas thus produced appears as unwanted fizz. Additional malolactic fermentation in the bottle or fermentation due to Brettanomyces can also cause fizz or gassiness. These are all accidents in the winemaking process.

Blake Bomben, a local winemaker, listed several factors that might provoke such an event, including non-sterile bottling, high pH or low alcohol that promote leftover yeast, as well as other contaminants such as malolactic bacteria or Brett. Bad cooperage, with wine stored in contaminated barrels can be another factor.

Blake indicated that unwanted secondary fermentation in red wine is almost always an Old World phenomenon. This explains the Galernau, in which the fizz was most likely due to Brett induced fermentation. It also explained a most memorable experience I’ve had with not one, but six bottles of 2001 Gigondas, Domaine de Cayron, a Southern Rhone red. I encountered significant fizz through the first four bottles as I opened them over ten years, the cause of the secondary fermentation unclear.

Blake explained that in the U.S. almost all red wine (well over 90%) is subjected to malolactic fermentation to avoid problems like this. Since New World reds often have high residual sugar, they are more at risk of unwanted secondary fermentation. Winemaker induced malolactic fermentation is therefore a sound preventive measure. Malolactic is not just a means to achieve a desired flavor in white wine, but also a safety factor in red wine.

Blake added that Old World winemakers who employ techniques passed down over generations rarely engage in this practice and generally are more tolerant of contaminant flavors such as Brett or fizz.

True. But as the wine world globalizes and the Old World looks at the New for markets, this attitude is gradually changing.

With Brett contamination the answer is no. The wine is spoiled and should be discarded. As for others, I posed the question to Larry Johansen, owner of Wine Wizard’s. The only remedy, he said, is to lay the bottle down and wait for the secondary fermentation to complete itself.

Is that possible?

I unwittingly experienced this with my 2001 Gigondas. A fifth bottle that I opened this year was finally fizz free. It took over a decade for the unwanted fermentation to terminate.

Unwanted secondary fermentation is an unintentional event, in some ways akin to a mishap in my own world of surgery: foreign objects forgotten in the human body such as sponges or surgical instruments. These are nowadays considered never events in medicine, with numerous preventive measures undertaken. The wine world does not have a similar concept, the stakes not being as high. Most consumers who encounter unwanted fizz in a bottle simple discard it and never complain.

Maybe the wine world should also embrace the concept of never events.