In one of the more surreal events of my years in the English High School of Istanbul, I came face-to-face with Princess Anne, the daughter of Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain. The year was 1971 and it happened in, of all places, a chemistry lab.

In the early and mid 20th century the English High School was a bright beacon of British culture among Turks. The Brits never colonialized Turkey but, as the dominant world empire of the early 20th century, they exerted significant influence over the country, contributing to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. A new, secular Turkish Republic that emerged from the ashes of the Ottomans charted its own course, eventually aligning with the U.S, the new dominant western power. By the 1970s, when I attended EHS, our elite prep school occupied a tiny role in British-Turkish relations, in line with the then decreased influence of Great Britain as a world power.

The school was in serious decline. It had lost British subsidies and was in dire financial shape. In the late 70s, after I graduated, it would completely fail and be converted to a Turkish school called Nişantaşı Anadolu Lisesi.

It was at this inauspicious time that Queen Elizabeth II, planning a state visit to Turkey, decided to drop by our school. Why, I don’t know! The school was meaningless to all parties involved except, perhaps, as a symbol of old, more glorious days.

The news, announced months in advance, caused major excitement in the school body. Why? Again, I nowadays don’t know. But at the time it was obvious. The Queen was coming! Did we need any other reason?

As the school became impoverished, it lacked adequate funds to furnish state of the art science labs suitable for the budding scientists that most of us were. In a society that highly valued a technical education, the lack of proper physics, chemistry and biology laboratories to supplement the lecture courses in these fields – obligatory for all – was disconcerting.

By contrast, other elite schools, including the wealthy Robert College, an American school located in a gorgeous campus on the hills overlying the Bosphorus, seemed to have everything, including those much coveted labs.

Half of our class that started Ortaokul (grade school) at EHS in 1967 had recently defected to Robert College for Lise (high school). They were the best and brightest. Those of us left behind felt bewildered and abandoned. It was a declaration that EHS was in decline and a better education was to be had elsewhere. We felt inferior to our American counterpart. In retrospect, the two schools were a microcosm of the post World War II reality that their parent countries represented.

We were too young to appreciate the metaphor. All we knew was that there were gaps in our science education. We wondered how much better we would turn out if these did not exist.

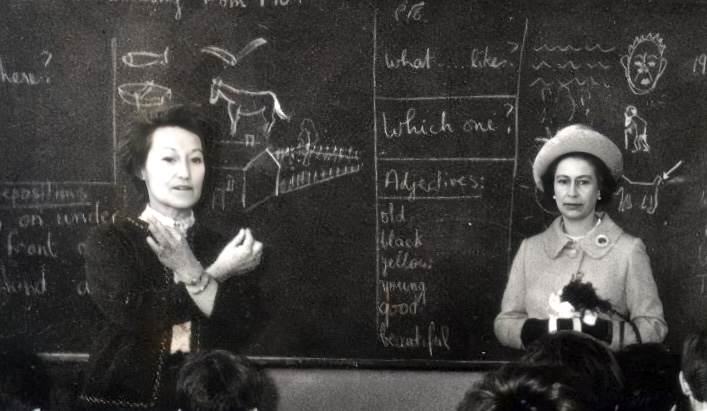

As the royal visit approached, the leaders of EHS set out to sweep the school’s inadequacies under the rug. They intended to present the queen with a perfect, well rounded, up-to-date prep school, injecting ostentatious British culture to the elite progeny of Istanbul. The show they planned included a chemistry lab demonstration, as if the school carried this in its regular curriculum.

As the visit loomed closer, preparations took on increased urgency, everyone rehearsing at a progressively furious pace. It was as if we were staging a major school play.

Our chemistry teacher was a young Turk, as it turned out in more ways than one. A recent alum of EHS, he was in an interim job on the way to bigger and better things. He was a breath of fresh air, injecting energy and enthusiasm to a subject that previously languished under lackluster British predecessors.

His name was Mehmet Ipekçi. He cut a dashing figure in the school, tall and handsome with a grand moustache and the temperament of a young army officer. He was strict, thorough and intimidating, the perfect epitome of a future leader.

Mehmet Bey belonged to an illustrious family from Thessaloniki who were said to be dӧnme, a Jewish group that had converted to Islam in prior generations. It was a section of society viewed with suspicion and likely to encounter glass ceilings in their careers, especially in politics and the military. His uncle was a famous journalist Abdi Ipekçi, who, before the end of the decade, was to be assassinated by the infamous Mehmet Ali Agca, better known as the assassin who attempted to slay Pope John Paul II in 1981. The younger Ipekçi, fearless and full of vigor, seemed destined to shatter any glass ceiling in his way.

He was also a proud man who did not take to any humor at his expense. Once, a classmate named Selim, a science geek with a strong interest in theoretical physics and chemistry, himself carrying a great ambition of becoming the next Einstein, had left the chemistry teacher a message on a blackboard. It happened after Mehmet Bey abruptly shaved off his imposing moustache in the middle of the school year, shocking us all with a new, puerile image.

In those days the students stayed put in a given classroom while the teachers moved around to deliver their lessons. There was always a 5 or 10 minute break between classes, idle time ripe for mischief. On such an occasion, Selim delighted us with a poetic line he chalked on the blackboard: “Bıyıksız Mehmet kuyruksuz eşege benzer.” Mehmet without a moustache resembles a donkey without a tail. In Turkey donkey is a mild swear word.

When Mehmet Bey entered the class and saw the writing on the board, he did not take well to having his visage compared to that of a donkey’s ass. He hit the roof and insisted on knowing the identity of the messenger. The culprit was soon revealed, and from then on he gave Selim hell for the rest of the school year.

Upon receiving the mission to put on a chemistry show, Mehmet Bey came up with a simple, impressive demonstration that was least likely to blow up the lab – and the royal visitors. It was an acid-base titration where, as the pH of the reactants changed so did their color, in a magical, artistic transition.

In those days I was a science geek, a fact well known to the teaching staff. I quickly got assigned to this lab. My mate Selim, much to his disappointment, was excluded. That tailless donkey was to hound him for months to come. A group of bright science students, assembled for the royal demonstration, repeatedly practiced the titration experiment in a makeshift chemistry lab at the top of the school building, acquiring facility with it.

We were pleased that the occasion of the royal visit had given us a rare chance to practice the lab experience we sorely lacked.

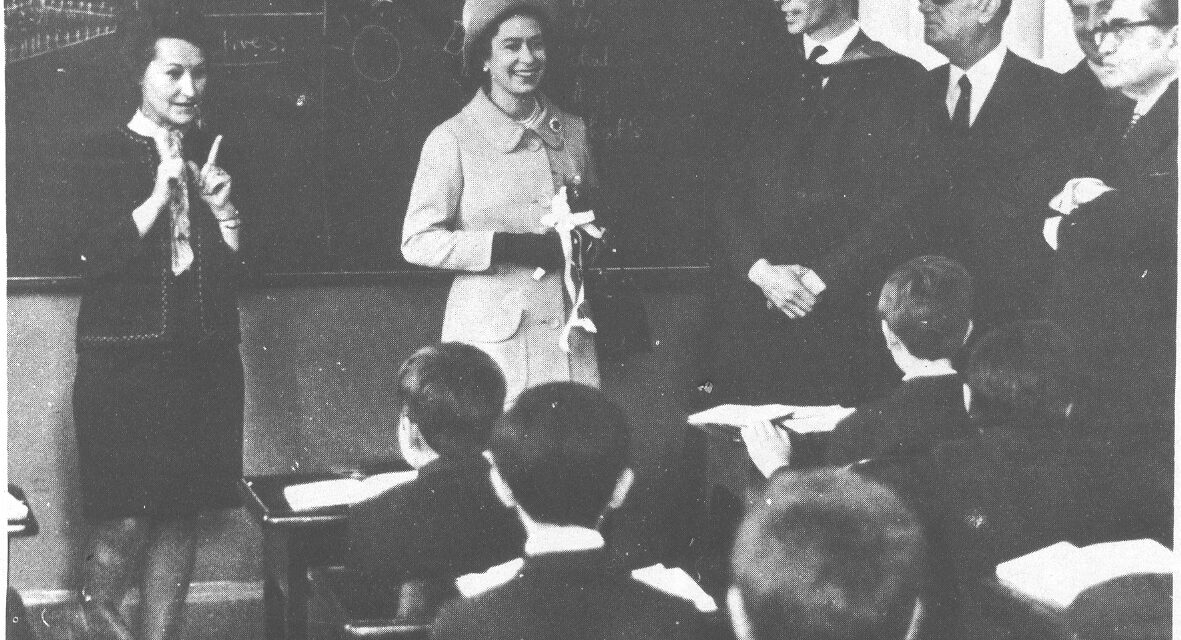

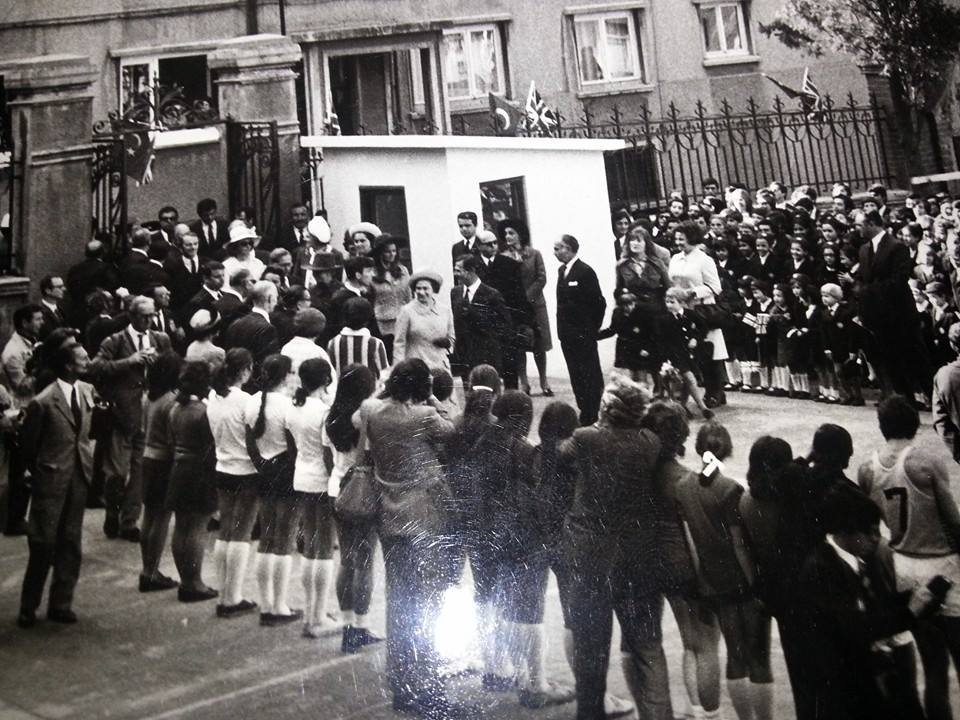

After months of anticipation the much-awaited day arrived. The Queen showed up with an entourage that included her then young, unmarried daughter Princess Anne. She was received by the entire student body gathered in the dusty schoolyard, lined up in military formation. They too had practiced their routine countless times, as we had with our acid-base titrations.

Those of us assigned to the lab were happy to be excluded from the tedium of standing at attention in the yard. We crowded the windows of the lab and observed the royal inspection of our fellow students down below. When Queen Elizabeth entered the yard, accompanied by the Mayor of Istanbul Vefa Poyraz and other dignitaries, all we saw was the top of Her Royal Highness’ hat, slowly wading through the thicket of students. The hat was pink.

Queen Elizabeth did not come to our chemistry lab. Perhaps the four story climb to the attic was too much for her. The school had no elevators. Instead, she sent her young daughter for whom those stairs were, I suppose, no trouble.

Thus, one day in 1971, at age 15, I witnessed the grand entrance of Her Royal Highness Princess Anne of Great Britain into our humble chemistry lab where, with a well-timed cue from an advance observer, we had initiated our titration some minutes earlier. We were attempting to time that all important, theatrical pH change to her royal arrival so that she did not experience much ennui in the few minutes it takes for the reagents to mix in the beakers.

This we managed with much flair. The students stood in groups around a rectangular bench and pretended to be preoccupied with our experiment while keeping a keen eye on our distinguished visitor. The princess circled us, observing the proceedings with obvious disinterest.

She was much prettier in person than in newspaper and magazine photos where she appeared plain and horse faced. I distinctly remember thinking that if she stayed in the room a few minutes longer I could develop a crush on her. My surprise at how pretty I found her is indelibly etched in my memory of that day. Was I just a horny, hormone crazed teenager who would have found any woman her age attractive? I will never know, for I have never met her again.

She completed her inspection as fast as she could and muttered something under her breath, soft but audible, about how much she disliked chemistry. Within seconds she was gone.

We immediately rushed the windows to catch a glimpse of her mother, still at the yard with her large entourage, engaging in some ceremony or speech. Our unfortunate school mates remained at attention in neat rows. We stared at the top of their heads, and Her Royal Hat, trying to make out what was being said. High atop the building, amid the din of the city, this was impossible.

That’s when the second most memorable impression of the day happened quite unexpectedly and nearly erased my budding romance with the formerly plain, now pretty princess. In the safety of the lab, high atop the proceedings, Mehmet Bey went into a lengthy tirade about what a useless woman Queen Elizabeth was, and how anachronistic the British Monarchy had become in modern times. This he did with all the passion of a Young Turk properly indoctrinated with the tenets of Atatürk, father of our country. He projected his hatred of the Ottoman monarchy, a central tenet of Atatürk’s Republic, on this hapless woman which for us was nothing but a pink hat viewed bird’s eye.

Mehmet Bey’s fervent rant was not solely his, but rather that of a Western leaning intelligentsia of our new, fledgling nation. The Ottoman monarchy was a symbol of Medieval backwardness, illiteracy and tenacious, dogmatic attachment to Islam, impeding the rapid enlightenment so vital for the effort to catch up with the West. For Mehmet Bey the Queen was nothing but a fellow felon, a sister of the Abdulhamits and Abdulmecits of the past.

I did not understand all this then. All I remember was being stunned at his overt display of disrespect towards, of all people, the Queen of England. That the words were uttered by a teacher, an authority figure who commanded obligatory respect, made the occasion all the more shocking.

It was clear to me then, as it is now, that if Mehmet Bey had been within earshot of the school’s leadership, he would never have engaged in his rant. Arrogant as he was, he was not that daring.

The contrast between our collective excitement about the Queen’s visit and Mehmet Bey’s proclamation left me befuddled. Was the Queen really superfluous and anachronistic? Did she deserve respect?

I was to ponder these questions in decades to come, especially during a 1985 sabbatical when I studied neurology in London. When Princess Diana tragically died in 1997, I was surprised to see Mehmet Bey’s passionate opinions expressed around the world, including by the Queen’s own subjects. I was impressed with how prescient he had been.

Queen Elizabeth II lived a long life. A half century after the royal visit, on the current occasion of the Queen’s death at age 96, the world again ponders the issue posed by our chemistry teacher back in 1971. It continues to lack a definite answer.

EPILOGUE

Four years after the royal visit I was a freshman at the University of Chicago where, in another chemistry course, I performed the same acid-base titration as in 1971. I was now in one of the great Universities of the world, an institution with no financial problems. My pre-med curriculum was heavily science oriented. Much to my surprise, I discovered that my chemistry, physics, calculus and biology courses in Chicago were verbatim repetitions of what I had received in EHS, and in which I had excelled. I scored easy A’s in Chicago, for this was material I knew well.

Wouldn’t you know it? That EHS education that we denigrated as inferior was actually top notch, laboratories notwithstanding. In fact, those labs we so coveted turned out to be overrated.

MORIS SENEGOR