“Wow, you must have a nice camera!”

This the a most annoying comment I receive when someone is impressed with a photo I took. It’s also the most common. I usually make some brief remark like, thanks or I do, and try to hide my irritation.

It takes a lot more than a nice camera to create great photos. It is the person behind the camera that counts most. An experienced photographer can do wonders with a basic cell phone while a novice might fumble with tens of thousands worth of equipment.

So what does it take?

First and foremost one has to have a clear understanding of basic technique such as aperture (aka f-stop), shutter speed, ISO, auto-focus, lenses, and how to use these toward a desired goal.

One also has to understand light and how it impacts a certain scene. Bare sunlight may light a scene well, but can cast harsh shadows. An overcast sky may be gloomy but display better details of a subject. You shoot with the sun to your back…Basic rule. But what if you shoot at the sun? You can get dramatic silhouettes with the right foreground subject, or an amazing sunburst if the sun is emerging from the shadows. Understanding how to manipulate light toward an artistic goal is a never-ending quest.

Composition is crucial. There are basic compositional rules such as placing the dramatic focus of the photo in the intersection of the thirds or blurring the background with a low f-stop to highlight the foreground subject in sharp focus, also known as manipulating the depth of field.

But composition is not governed by rules as in baseball. There is a good deal of freedom for experimentation and self-expression.

How does one learn composition? I can’t speak for others, but the way I did it was to start with the basics and then go on to study the great masters, not just in photography but also in painting. I visited countless museums all over the world, I bought art books and examined the masters. I compared how I would have displayed a scene versus how they did. You can do this for a lifetime and still learn new tips.

In the old film days photography was much more challenging. It was expensive. You had to pay for film and developing. Taking too many pictures was cost prohibitive. When the film came back from the developer you were stuck with the results, no cropping, no exposure adjustment.

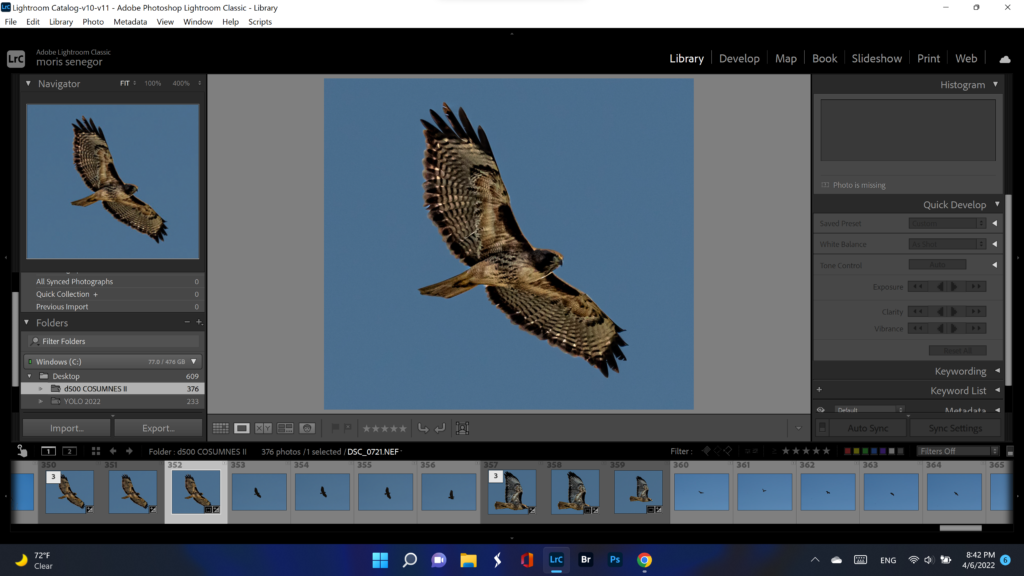

Nowadays you can take hundreds, thousands of photos without worrying about cost. You can bracket for variables such as f-stop or ISO with impunity. Many photos previously considered “defective” in the film age can now be salvaged in the digital age.

The ability to post-process with whatever software package you prefer (mine is Adobe Lightroom) is a major game changer. You can fix exposure and color balance, you can convert a color photo to black & white, you can crop, rotate, invert as you wish, and more… Much more.

As wonderful as post processing is, it creates a new challenge for wanna-be photographers. Knowing your camera and its variables is not enough. You also have to achieve mastery in a post-processing medium.

Post-processing adds yet another layer of challenge to composition. It is no longer sufficient to compose via the viewfinder of your camera. You also have to alter or enhance your composition during post, and this requires a vision, a dramatic goal.

It is easy to over process, something akin to too much make-up. The results look fake and gaudy. Just look at the multitude posting on photo intensive social media such as Instagram or Facebook. There are tons of examples. You can take heed and hold your own reins back.

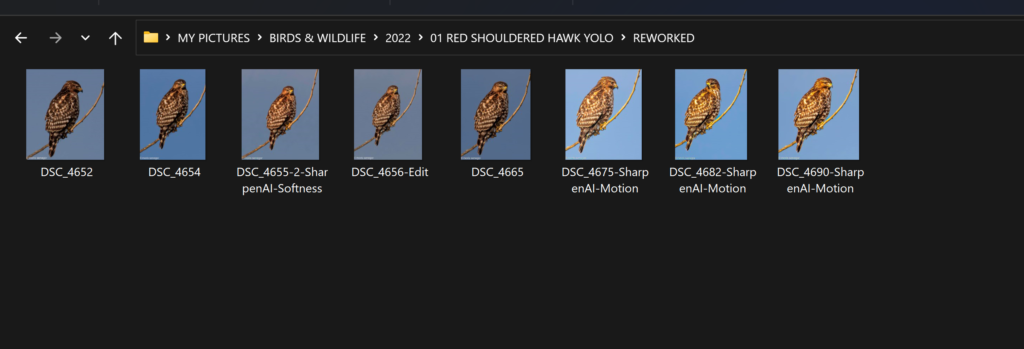

Finally, there is an aspect to photography that, in my opinion, is the toughest challenge: knowing which photos to display.

Modern cameras and post processing software create a problem of riches. One ends up with too many decent pictures. Every photographer is in love with every good picture he/she produces. They want to display them all. They can’t.

The fewer that are displayed, the better. Only the best of the best.

This is where many good photographers fail. They show too many and thereby dilute the dramatic impact that could have been achieved with one or two. Acquiring restraint in display is the ultimate challenge.

To those, “you must have a nice camera,” folks, I say, “You have no idea what it takes.”